Ryu Sungsil is a South Korean artist who was included in the Frieze Art Fair’s list of young talents to watch out for. We talked to the artist about her work and how it addresses the problems of contemporary Korean society, and Natalia Serkova, philosopher and co-founder of Tzvetnik, wrote a commentary reflecting on her artistic practice.

Text: Natalia Serkova

Through her artistic practice, the South Korean artist Ryu Sungsil illustrates one of the problematic principles of the international contemporary art environment. The main theme with which Sungsil works is the reflection of a representative of South Korean society on the harsh neoliberal reversal that took place in Korea in the mid-twentieth century and is still gaining strength. Demonstrating in her projects how elements of “deep” Korean perception collide with westernized consumer ideology, the artist ironically and sometimes even wryly reveals the contradictions caused by this social collision.

Characteristically, the artist herself has been able to raise this topic at a high professional level because she was able to get a professional art education, which, according to her, is only available to the wealthy in Korea. Coming from a Korean family that earned its fortune in the penultimate generation (Ryu’s parents moved up the social ladder), the artist was able to publicly reflect on social inequality and the negative aspects of capitalist ideology. Thus, as a privileged member of Korean society, Sungsil chooses the path of an artist and speaks about the sociocultural characteristics and problems of her country.

This recursive situation – where it is the privileged artist who finds herself able to speak out about issues of privilege and be heard (30-year-old Sungsil was recently named one of the rising stars by Frieze Fair) – is deeply characteristic of the current contemporary art system. We may have different views on such recursion – and even invoke the very conceptual logic of contemporary art (after all, autoreferentiality of all kinds has been popular in art for at least the last 150 years) – but sometimes it is at least useful to examine an artist’s practice from this angle. Not to denounce the artist himself, but to see how deep the contradictions as such are in principle deepened in the art system at the current moment.

Perhaps it is the attempt to analyze this and many other systemic contradictions that will help us understand what the art of the 2030s will look like, and suggest what language artists will speak in the future and what sociocultural input will be required of them in order to be heard. In this sense, Sungsil is a great example of an author whose background, talent and energy can contribute to such an understanding on our part.

First, tell us about yourself: how did you get started in art and what do you think are the main themes you uncover along the way?

I am a visual artist based in Seoul, and my interests lie mainly in observing the clash between traditional Korean culture and neoliberalism. I utilize various media in my work: videos, installations, and performances.

I was fortunate to have parents who financially supported my artistic endeavors since childhood, especially considering how much money it costs to study art in Korea. It should be noted, however, that their support was not motivated by any deep love for art or respect for my interests. Rather, it was based on a desire to maintain my newfound wealth and high social status. The fact is that Korea’s elite art education system is quite unique: specialized private middle and high schools are dedicated to the comprehensive training of young talents to become artists. However, although I personally have benefited greatly from this education as a professional, these schools are rather known in society as institutions for the privileged class. My parents, who came from a poor rural family, apparently hoped that my inclusion in such an “elite institution” would help them realize their social ambitions. It was funny: they imagined that I would marry a rich man and live a privileged life, but instead I actually became an artist.

Almost all of your works are socio-political in nature, and you regularly create sarcastic images that mock the capitalism of Korean society. Can you explain to viewers who are far from Korean reality what attracts you most to social issues and what contradictions of contemporary Korean society do you try to reflect in your works?

As the Koreans say, “Korea doesn’t produce a drop of oil, so our only resource is human beings”. I’m not sure if this is only true in countries where people are exploited to make up for the lack of natural resources or if it’s true everywhere, but I’m honestly afraid that someday I’ll burn like firewood myself…. At the same time, I realize that as someone born and raised in Seoul, I myself embody this unique sense of Korean “high-speed living” – which, however, makes me neither happy nor proud. I’m trying to work on that feeling.

At the last Frieze, you were listed as one of the ten most interesting Korean artists. Are you making your way more as a solo artist or are you represented by any gallery?

I have had the experience of exhibiting in selected good galleries in Korea and abroad, but I am not currently represented by any gallery. I understand the pros and cons of working with a gallery and am open to the possibility in the future, but for now I am happy with the status quo. My work is often exhibited in public art museums, but I mainly distribute my work through popular online communities. As a result, when people in the art world talk about my work, they mostly mention its unique position – somewhere on the path between the Internet public and academic art. Personally, I’m interested in working to find a balance between established art audiences and the general public – especially those who hardly visit museums.

In the future you will surely be involved in many art residencies around the world. Will you continue to work with Korean identity, will you try to uncover poignant themes in Western societies, or will you radically shift in some other direction?

I can only talk about the experiences I have had myself. Since I have not yet encountered the problems of Western society in my life, I cannot “force” myself to address them in my work. In the end, however, despite our different sociocultural contexts, we are all residents of a single world community linked by the global economy. For example, a relative of mine, living in a remote Korean village and farming, lost all his savings in 2008 when the bank where he had kept his savings went bankrupt. He did not understand anything about the causes of the financial crisis, but that did not prevent him from suffering the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Finally, please tell us about your most recent work or a particularly important exhibition for you.

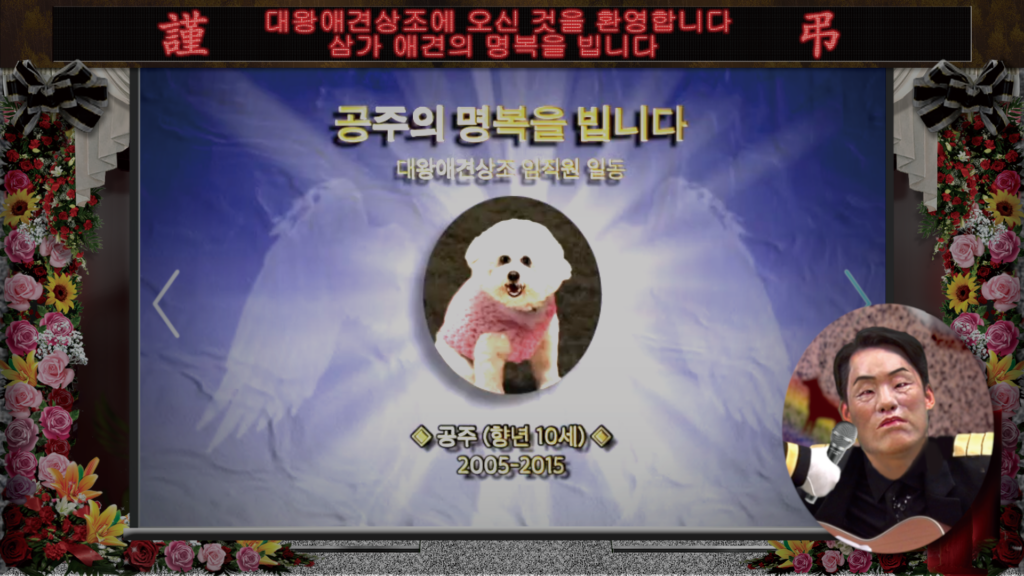

My exhibition, The Burning Love Song, was held at 2022 in the basement of the Atelier Hermès gallery, the Hermès Foundation’s space dedicated to Korean art. For the exhibition, the gallery space was “disguised” as a pet crematorium organized by a fictitious company called Big King Pet Funeral Service, where visitors were invited to participate in the mourning of deceased pets.

On a large screen on the wall of the “crematorium” every 15 minutes a video was repeated, which demonstrated the company’s business acumen (on the verge and beyond absurdity) – capable of turning death itself into a consumer product. Mr. Big King, the owner of the company, declares in the video that he is more interested in art than money, and sings a tearful song “True Love” for the guests. Meanwhile, his female employee, painted as a shaman, acts as a “communicator with dead animals” and pretends to be possessed by the spirit of a dead dog. In general, the exhibition suggests that in capitalist societies a person’s place in the hierarchy is determined not by his social background, but rather by his thirst for profit and his ability to think outside the box.